- Home

- Shannon Hale

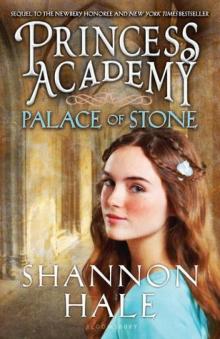

Palace of Stone

Palace of Stone Read online

PRINCESS ACADEMY

PALACE OF STONE

SHANNON HALE

For my Dinah

A princess in her own right

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Acknowledgments

Also by Shannon Hale

About the Author

Chapter One

The rock-lined road is the way to work

The rock-lined road takes the work away

The rock-lined road is the way to take

If you take that road away you’ll always take that way back home

Take you there and take you home, there’s nothing but the rocky road

Miri woke to the insistent bleat of a goat. She squeaked open one eye. Pale yellow sky slipped through the cracks in the shutters. It was day—the very day trade wagons might come to carry her off. She’d been expecting them all week with both a skipping heart and a falling stomach. Strange, lately, how many things made her feel two opposite ways twisted together.

Peder was like that.

Miri crept from her pea-shuck mattress to the window. A figure stood in the doorway of Peder’s house. She waved, Peder waved back, and those addled feelings popped inside, her chest light and excited, her head tight and unsure.

She felt two ways about home too, she realized, looking out at the few dozen houses of Mount Eskel, their roofs traced white with dawn light. Her mountain was big. The world was bigger.

A noise called her back. Her sister, Marda, was sitting up, and her pa too, stretching and groaning from the ache of sleep. For them she felt only one way. And for them she never wanted to leave.

Miri talked while she helped Marda stack the mattresses to clear the floor, and talked while she dished up breakfast, and talked while she led the goats from the adjoining room into the sharp light of morning. If she talked, she did not have to think. Thinking only made her stomach fall faster.

“Peder’s grandpa says he’s seen more bees this fall than he can ever remember, and that means the winter won’t be too hard, but if it freezes and thaws all the time you’ll have ice everywhere, so I think we should dump more gravel on the path to the stream—”

“We’ll be all right, Miri.” A goat pushed against Marda’s side, and Marda rubbed its ears. “You don’t need to worry.”

Pa was walking ahead of his girls. His back tensed against Marda’s words.

“Pa …,” Miri said. She wanted him to say that he would be all right without her.

They reached the quarry, a huge bowl of white stone, rectangles of rock jutting at odd angles. Already dozens of villagers were squaring blocks of linder stone they’d cut from the mountain and were hauling them out of the quarry. The nearest group worked one stone together, singing to keep in rhythm: “Take you there and take you home, there’s nothing but the rocky road.”

Pa halted at the edge. “Expect us for lunch, Miri, so long as …”

Miri finished his thought. So long as the wagons have not come.

Pa hefted his pickax and strode into the pit. Marda followed, turning to shrug at Miri. Miri shrugged back. They both knew their father’s temperament.

Miri tied her goats on a slope where they could graze, then skipped back down to the house. She picked up a letter from the table, as she had each morning since it arrived with the traders in the summer. The letter still seemed as magical as books had when she’d first learned to read.

She had the letter memorized, but she read it again anyway. It was from Katar, who had left Mount Eskel for the capital several months before.

Addressing Miri Larendaughter, Lady of the Princess,

Mount Eskel

Miri,

This is a letter. A letter is like talking to someone who is far away. Do not show the others in case I am doing it wrong.

This fall, extra wagons will go with the traders to bring to Asland any academy graduates who are willing. You are invited to stay one year. I know you, at least, will come. It is a long trip. Bring a blanket to sit on in the wagon or you will get a bruised backside.

At harvest, each province in Danland presents a gift to the king. As this is the first year Mount Eskel is a province, I want our gift to be really fine. I cannot think what we can offer besides linder. I do not think goats would be quite right. Please tell the village council that the linder must be special, perhaps a very large block of it. I do not sleep well with worry. I grow tired of the mocking way the other delegates speak of Mount Eskel.

I am anxious for you to come. There are things happening in Asland. I need advice, but it would be dangerous for me to write about it, I think. I hope it will not be too late by the time you arrive.

This letter is from Katar, Mount Eskel’s delegate to the royal court in Asland

Miri put the letter back on the table, held down by a shard of linder—white stone struck through with veins of silver. She could not guess what dangerous matters Katar wanted to discuss with her, but that had not kept her from trying to imagine all summer long. And summer had seemed very long indeed.

Miri picked up a second letter and could not help smiling as she read Britta’s looping handwriting.

Miri Larendaughter, Mount Eskel

Dearest Miri,

I am delighted to write to you! Though I would rather talk to you in person and sit as we used to do in the shade of the princess academy, watching hawks glide. At least I have good news to share. The king has invited the academy girls to come this autumn! Autumn is not near enough for impatient me, but it is closer than next spring.

I will brag just a little and claim credit. I made a very pretty argument that the mountain pass might still be stopped with snow in the spring and prevent you from arriving in time for the wedding. And how could the princess be married without the princess’s ladies?

You girls will room here at the palace. Palace seamstresses will make you dresses in the Aslandian style, so please do not fear on that account.

Also, I have wonderful news! There is an open spot for you at the Queen’s Castle, the university I told you about. Studies begin after harvest, so you see, another reason I am eager to have you here before spring.

More good news. A stone carver my father used to hire has agreed to take Peder into apprenticeship. Gus will house and feed Peder in exchange for a year’s labor and one block of linder.

There will be so much for us to do here. I can scarcely sleep sometimes for daydreaming! Let the summer fly on hot, swift wings.

Your friend,

Britta

Traders came up to Mount Eskel only once each spring, summer, and fall, so Miri had been unable to reply to either girl. She had no doubt Katar was going crazy with worry about their gift for the king. Miri could not wait to surprise her.

Miri ladled morning gruel into a pot and headed out the door. Peder had spent the past three months sweating over the gift. And since his family was short one quarry worker while he labored, the other village families supported Peder with meals. Today was Miri’s turn. While her pa and sister worked in the quarry, Miri kept the house

and goats.

She ambled over the rock chippings that covered the ground to Peder’s house, knocking once and letting herself in.

“Good morning, Peder,” she began, stopping when she saw Peder’s father, Jons, standing with arms folded. The mood in the cottage had the bite of winter wind.

Peder slumped onto a stool. “My father is reconsidering letting me go to Asland.”

“Not reconsidering,” Jons said. “Decided. You’ve already wasted three months carving this thing. Since your sister is leaving us, you’ll be staying.”

For Peder, quarry work was mindless, endless. He’d been carving bits of linder into animals and people for years, yearning for a chance to do it more. Miri wanted to plead with Jons but checked herself, remembering the rules of Diplomacy she had learned at the princess academy.

“I can understand, sir, why you want Peder to stay. He hasn’t worked in the quarry since the summer traders came. Besides, it would be hard on your family to lose both children for a year.”

“Just so,” he said, squinting suspiciously. “It’s impossible.”

“I would agree, but in this case, sending Peder to Asland will be much more useful for your family and the village in the long run. As it is now, after the traders haul our stone down the mountain, artisans in Asland chip away half of it to make mantelpieces and tiles and such, and they earn a good living doing it.”

“Exactly!” Peder said, standing up. “Why shouldn’t we do that work here, ourselves? After I’m trained, traders could bring me orders in the fall, then I’d work through the winter and send the carvings down in spring.”

“Traders can haul twice as much finished stone as rough stone,” said Miri, “which would mean twice as much pay for everyone.”

Jons narrowed his eyes further. Miri swallowed but asked the final question.

“I know Peder will be diligent in his apprenticeship and do you proud. Will you let him go?”

She held her breath. She could not hear Peder breathe. Jons turned to look out the window.

“Fine,” Jons said with a grunt. He paused to lay his hand on Peder’s head before leaving.

“You’re amazing!” Peder said, hugging Miri.

He took a step back and smiled as if he truly loved looking at her face. Then he started in on the breakfast.

Why doesn’t he ask? The thought was so well used it squeaked in Miri’s mind like dry hinges. She was of age to be betrothed. Peder seemed to like her and no one else. Yet he did not ask.

Afraid to look at him in case he could read her thoughts in her eyes, she leaned over the mantelpiece he’d been carving. She traced the images of Mount Eskel and the chain of mountains beyond, beautifully captured in linder.

“It’s smoother,” she said.

“I’ve been polishing it.”

An unmistakable sound reached them from outside. They rushed to the window to see the first in the line of trader wagons, crunching rock debris under metal-rimmed wheels.

Miri was holding Peder’s warm, callused hand. She did not know who had reached out first.

They ran to meet the wagons, along with most of the village. Trading began, families selling cut blocks of linder and purchasing foodstuffs and supplies from the wagons. In the past, trading day had been an anxious occasion, each family bartering for just enough food to avoid starvation. But since the previous year, when the villagers were first able to sell their linder at fair value, trading days had become festivals.

Children danced in excitement over ribbons and cloth, shoes and tools, bags of dried peas still in their shucks, barrels of honey and onions and salt fish. Such items had always seemed magical to Miri, evidence of fabulous, faraway places. How often she’d daydreamed of cities, farmlands, and endless ocean. Now at last she would go. But she did not feel like joining in the dance.

Peder caught up with his mother to help in the trading, and Miri sold her family’s stone. Then she went in search of her sister.

“Please come, Marda,” she said, panic tightening her throat. Marda was not an academy graduate, but she knew Britta would not mind, and the other girls adored Miri’s gentle sister. “I thought I wanted to go, but I’m scared. I need you. Please.”

“You’re not scared,” Marda said quietly. “Or you won’t be for long.”

“Marda, I’m serious.”

“I’m not like you, Miri. Learning about all those places and past kings and wars, it makes me feel like … like I’m sleeping on a precipice. I don’t like that feeling. I want to stay home.”

“But—”

“Pa and I both know you’ll be fine. So fine, in fact, he worries you won’t come back.”

“He does?”

Marda nodded. “So do I.”

Miri shook her head. She could not imagine staying away forever by choice, but so much could happen in a year, so many obstacles to coming home. And what dangerous matters did Katar fear? Miri felt her chin start to quiver.

Marda rubbed Miri’s back and forced a confident smile. “A few blinks and you’ll be back. A year’s a small thing.”

Marda’s words reminded Miri of a line from a poem she’d read in one of the academy books, so she said, “No small thing, a bee’s sting, when it enters the heart.”

“A bee’s sting entered whose heart?” asked Marda.

“It’s just a poem. Never mind,” Miri said. She should have known Marda would not understand, and that made her feel as lonely as if she were already gone.

Marda put her arm around Miri, tucking her head against her own. Miri noticed her sister had grown taller in the past year. She was older than most Mount Eskel girls who accepted a betrothal, yet no one had spoken for her. Once all the village boys were betrothed, no others would come rushing up from the lowlands to take their place. And Marda was too shy to speak for herself.

As soon as she returned from Asland, Miri decided, she would be matchmaker for her sister. And she’d keep teaching in the village school till every villager could read, including her pa. She felt better making plans like ropes securing her to her mountain.

The trading hurried along, culminating in the trading-day feast. Now it was a farewell feast.

Not all the graduates of the princess academy would be going. Some were kept back at their parents’ wishes; others had accepted betrothals and did not want to leave. Miri would travel with five girls: Gerti, Esa, Frid, Liana, and Bena. Each carried a burlap sack filled with her few possessions. Miri clutched her own sack to her chest. The summer had seemed endless, but now that this moment was upon her, it felt sudden and sharp, a hawk in a hunting dive.

“I’ll write to you,” she told Marda. “Every week. And I’ll send the whole stack of letters with the spring traders. And the letters will all say the same thing—I miss you, and I’ll be home next fall. Home for good.”

Marda just nodded.

Her father approached, his hands behind his back, his eyes on the ground. Miri stepped forward to meet him.

“Don’t forget to butcher the rabbits come high winter, when the pelts are thickest,” she said. “It breaks Marda’s heart to do it, and if I’m gone …”

He glanced at her and then away again, frowning into the chain of mountains: brown, purple, blue, and beyond, ghostly gray summits seemingly afloat above the clouds.

“I will come back, Pa,” she said.

“I wonder,” he said in his low voice. “I wonder.”

“I promise.”

He picked her up, pressing her to his chest as easily as if she were still a baby. How could an embrace make her feel exquisitely loved and yet heartbroken too?

“I’ll always come home, Pa,” she said.

But a shiver of uncertainty had entered her.

Miri sat in the back of a wagon as it drove away, her eyes taking in every last image of home: her house built of gray rubble rock, the white gleam of linder shards marking the paths, the jagged cliffs of the quarry, and the magnificent, white-tipped head of Mount Eskel.

&

nbsp; She felt night-blind and afraid, as if walking a path that might lead to sheer cliff and empty air. The lowlands were so far away, she could hardly believe they existed. Once she was in the lowlands, would home seem like a dream too?

She glimpsed Pa and Marda one last time before the road bent and, quick as a sigh, the village was gone from sight.

Chapter Two

The city of the river

The city of the bay

The people of the limestone

The people of the clay

Miri’s jaw ached from gaping. First, there were the lowlander trees, their enormous leafy crowns still so vibrantly green it hurt her eyes. Next, farmlands stretched so far they curved with the world, green and golden. Then the wagons rolled onto actual streets, past wooden houses winking with glass windows. The roofs were made of thatch or tile with the occasional one of beaten copper—some new and orange but most a weathered green.

Trying to keep her voice steady, Miri said, “So this is Asland.”

Enrik the trader rolled his eyes. “No, this is just a town.”

That night they camped outside the town. Miri looked up from her supper of bacon and potatoes and met eyes with a thin girl, chewing on a stick. The town girl did not speak, just watched Miri with wide eyes. Had she come to see the backward folk of Mount Eskel? Would she run home and make fun of the way Miri ate? Miri hunched her back and turned away.

By the third day, Miri was accustomed to the rhythm of the journey: woods, farms, town, repeated again and again, the shuddering lope of the wagon constant beneath her. She rarely gaped anymore and almost forgot to be afraid until the day they entered Asland.

The rain began as a mist and thickened into annoying pecks on their faces and hands. Soon it was an onslaught, and the girls huddled together under an oiled cloth in the back of Enrik’s lurching wagon. Miri’s stomach squelched.

When Bena made sick noises over the side of the wagon, Miri scrambled forward and out from under the cloth, into the rainstorm.

“Death would be better than riding under there,” she announced. “Death or rain.”

The Princess in Black and the Perfect Princess Party

The Princess in Black and the Perfect Princess Party The Princess in Black and the Hungry Bunny Horde

The Princess in Black and the Hungry Bunny Horde The Unfairest of Them All

The Unfairest of Them All Forest Born

Forest Born 2 Fuzzy, 2 Furious

2 Fuzzy, 2 Furious The Actor and the Housewife

The Actor and the Housewife The Goose Girl

The Goose Girl Palace of Stone

Palace of Stone Midnight in Austenland

Midnight in Austenland Enna Burning

Enna Burning Dangerous

Dangerous The Storybook of Legends

The Storybook of Legends Princess Academy

Princess Academy Austenland

Austenland The Forgotten Sisters

The Forgotten Sisters The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl: Squirrel Meets World

The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl: Squirrel Meets World Book of a Thousand Days

Book of a Thousand Days Fire and Ice

Fire and Ice The Princess in Black Takes a Vacation

The Princess in Black Takes a Vacation River Secrets

River Secrets The Princess in Black

The Princess in Black Books of Bayern Series Bundle

Books of Bayern Series Bundle True Heroes

True Heroes Austenland: A Novel

Austenland: A Novel The Princess in Black and the Science Fair Scare

The Princess in Black and the Science Fair Scare![[Bayern 02] - Enna Burning Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/bayern_02_-_enna_burning_preview.jpg) [Bayern 02] - Enna Burning

[Bayern 02] - Enna Burning Ever After High

Ever After High Monster High/Ever After High--The Legend of Shadow High

Monster High/Ever After High--The Legend of Shadow High