- Home

- Shannon Hale

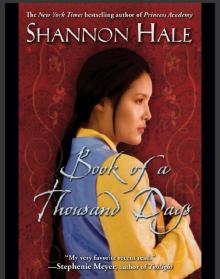

Book of a Thousand Days Page 2

Book of a Thousand Days Read online

Page 2

Then her honored father entered, and she stiffened and began to whimper as if fighting off a fit of sobs. He had one crooked leg. This surprised me fit to staring. I don't mean disrespect, but I'd always thought that gentry would be formed and perfect of limb, lovely and radiant, being the offspring of the Ancestors. But truth be, if her father had worn common clothing, I might've thought him a mucker. Either the Ancestors want it this way, or else Under, god of tricks, was deceiving my eyes.

"Still bleating about it, are you?" said her honored father. He was a man too small for his voice. "Titor and his dogs, girl—it's your mess. Crying about it is like rolling around in your own filth."

He watched her for a moment, and I swear by Titor and his dogs that there was a touch of sympathy in his eyes. I'd have sworn it on my mother's memory till he up and slapped her face. It didn't make sense, as though he slapped her more from duty than anger.

Mama used to say, "Hitting is the language of cowards and drunkards," and here a member of the honored gentry struck his daughter for crying.

"What's this thing here?" he asked, looking at me now, taking in my rough boots, my wool deel, my leather sash. "Why is one of your maids dressed as a mucker? Are you a mucker? Answer me, girl."

I answered him. "Yes, my lord, I was born on the steppes, and when I came to my lord's city last year 1 —

"That's enough, I don't want the whole story. You're nothing to look at, are you?"

I thought that was a useless question. I'm right aware of the red birth splotches on my face and arm, not to mention my dull hair and lips thinner than the edge of a leaf. Mama said that beauty is a curse for muckers. She once told me about Bayar, her clan sister, who looked like Evela, goddess of sunlight. And what happened to Bayar? A lord fell for her beauty, got her with child, then left both girl and baby in the mud and never returned. That's gentry's right, I guess, but it was a bit hard on Bayar.

"I remember now," my lady's father said with a humph, "Mistress Tolui said some mucker girl was coming from Qadan's. What a hell you walked into, though it can't be worse than your own home. Muckers survive on grass alone, just like sheep, isn't that right?"

"Well, my lord," I said, not sure how to contradict gentry, "we — "

He slapped his daughter's face again, suddenly and with no cause, like a snake striking. The sound of her cry was sharp and sad enough to break a bird's wing. It was then that I began to understand my lady — I think she must've lost her mother long ago, before she was old enough to learn how to comfort herself.

"There she goes again!" he said, his big voice booming out of his small head. "She'd gone quiet, and I've grown accustomed to her crying. Bawl all you want, wench! No one will hear you alone in the tower."

At that, she forced her tears to stop and looked right back at him, as brave as anything I've seen. "I won't be alone," she said. "My new maid is going with me."

"Is that what you think?" He was rummaging through her wardrobe, pulling deels from their hooks and tossing them onto the floor. "You don't deserve a maid, and I won't force one to attend you. So let me hear the maid say she's willing to go."

My lady was clinging to my arm.

"Go where?" I asked.

Her father laughed. "Now I understand." He took hold of one of the deels and ripped the sleeves off. "I, her honored father, have arranged an enviable match with Lord Khasar. He is the lord of Thoughts of Under, the most powerful of the Eight Realms. And does my daughter thank me? And appreciate her responsibility to form this alliance? No, she declares she's promised herself to Khan Tegus of the lesser realm Song for Evela. She refuses to marry Lord Khasar. How's that for gratitude? I'm sending her to a watchtower shut up as a prison and we'll see if seven years beneath bricks won't kill her rebellion. So say it, mucker girl, will you lock yourself up with this disobedient child?"

My lady was squeezing my arm so tightly now, my fingers felt cold. One of her cheeks was pink from his slap, her brown eyes red from crying. She reminded me of a lamb just tumbled out, wet all over, unsure of her feet and suspicious of the sun.

She'd be alone in that tower, I thought, and I remembered our tent after Mama died, how the air seemed to have gone out of it, how the walls leaned in, like to bury me dead. When Mama left, what had been home became just a heap of sticks and felt. It's not good being alone like that. Not good.

Besides, I'd sworn to serve my mistress. And now that her hair was fixed and her face washed, I saw just how lovely she was, the glory of the Ancestors shining through her. I felt certain that Lady Saren would never disobey her father lightly. Surely she had a wise and profound reason for stubbornness, one blessed by the Ancestors.

"Yes," I said. "I'll stay with my lady."

Then her father up and slapped me across my mouth. It almost made me laugh.

I'm right proud of myself for remembering so much! Maybe I got a few words wrong, but that's so near how the conversation went, I'm going to call it truth. My hand aches from writing and my ink grows thin from watering, so I'll finish for tonight.

Day 14

As my lady didn't budge from my mattress last night, I slept as I could on the sacks of barley flour in the cellar, but squeaks and scratches kept nipping at my dreams. When I woke from a nightmare and sat up, two tiny eyes stared back.

A rat. And where there's one, there must be more.

This makes me count numbers and rub my forehead. There's seven years of food for my lady and her maid. We don't have enough to spare for a family of rats. I found four sacks of grain with holes nibbled through and counted six tallow candles missing from a box. What if they eat more? A lot more? How will we survive seven years with rat-spoiled food and no light?

Day 19

Little time for writing these past days. When I'm not washing and cooking or singing and caring for my lady, I sit in the cellar with the broom and swat at anything with eyes. There are a dozen rats at least.

I don't have arsenic to make rat bread, so I fashioned a trap the best I could. Among our supplies I found some nails, as long as my finger and sharp, too. I drove them up through the lid of a barrel then lay atop the nails a piece of parchment. It looked a solid object to me, and to the rat as well, I suppose. Here's how it must've been:

I found it this morning, its body stuck inside the spikes with one nail up through its chin. I won't show it to my lady, save her. She is already feeling ill. I sang the song for stomachache but she grew tired of the melody and sent me away. I hear her upstairs rocking on her bed.

Sometimes I think there's something not quite right with my lady. She seems sad, but when I sing the song for sadness, she doesn't respond. Nor does the song for clear thoughts make her think straight. I guess a couple of songs just isn't going to be enough for whatever ails her. Mistress chose me because I know the songs, and now I begin to realize that my duty with Lady Saren will be more than just keeping her fed and clean. Perhaps the Ancestors sent me to heal her.

But what ails her? Could it just be she's that heartsick for her love, Khan Tegus? I can't wrap my thoughts around how deep their love must be. It's too high above me. It's surely a powerful love that bids a girl brick herself away from the Eternal Blue Sky for seven years. I once liked a boy named Yeke with kind eyes, but I wouldn't have given up the sun for him. Her khan must be such a man from legend, a man formed by Evela, goddess of sunlight. Perhaps if I looked at him, I'd have to squint. I'll ask my lady.

Later

My lady doesn't recall squinting..

Day 27

Not only have I been unsuccessful so far in healing my lady, she seems to have worsened. She spooks at sudden noises, like the wind getting hooked in the chimney or the wood floor whining under my feet. She startles and cries out as if each new sound were a cold hand grabbing her from behind.

Today while she lay upstairs, I heard a voice shouting outside, and I thought, Ancestors preserve us, but my lady's not going to like that. Sure enough, she poured herself down the ladder so fast, she fell to her

knees at the bottom. Not waiting to stand again, she crawled to me and clutched my legs.

"He's here, Dashti. Do something! He's here!"

I didn't know who she meant. I was certain the voice had been one of the guards who circles our tower, and I told her so.

"No, it's him, it's him."

"Who, my lady? "

"It's Lord Khasar." She stared at the walls as if expecting them to fall down around her. "He'll be furious that I refused him. He won't give up. I knew he wouldn't. In this tower, I'm a tethered goat left out for the wolf, and now he'll take me and marry me and kill me."

I held her and sang to her and let our dinner burn on the fire, and all the while she shook and cried dry tears, her mouth hanging open. I've never seen a person cry like that, with real fear. She made my blood shiver. I wish I knew what ails her, but perhaps it's too soon. Mama used to say, you have to know someone a thousand days before you can glimpse her soul. When the chill in the stones told us it was night, my lady's grip relaxed. She was so tired from shaking, she fell asleep on my mattress. I guess I'll be sleeping in the cellar with the rats.

I wonder what it is about Lord Khasar that makes her tremble fit to come apart at the joints. And I wonder if he really will come for her. But there's no sense in worrying about it. If he does come, we've nowhere to run.

Day 31

A few minutes ago we heard a voice. I dropped the robe I was washing and hurried to my lady, who clasped me so tightly around my neck I couldn't talk.

"It's him, it's him," she muttered, hiding her face in my neck. "I told you! It's Khasar and he's come back."

But then I really listened. The voice became clearer, and I heard it calling in a hush, "Lady Saren! Can you hear me? It's Tegus. My lady, I'm so sorry."

I gasped. "My lady! It's your khan — it's Khan Tegus!"

She stared at the wall. I expected her to run forward and cry for happiness to hear his voice, but she didn't move. Even now as I write this, my lady sits on my mattress, hugging her knees to her chest. And her khan continues to call.

"Go to him," I say. "You can talk through the flap."

But she just shakes her head.

Later

I'll do my best to remember exactly how it went.

It didn't seem right to keep her poor khan calling, his voice rasping in an effort to whisper and shout at once. Someone should answer at least. I fetched a wooden spoon and lodged it against the flap to hold it open.

I was just about to speak when my lady leaped at me, covering my mouth with her hand.

"What will you say? " she whispered.

"What would you like me to say?" I asked under her fingers.

My lady removed her hand and started to pace and fret and rub her head. She looked as if she'd like to run away, had there been anywhere to run. My poor lady.

"Say you are me."

"What? But why, my lady?"

"You are my maid, Dashti," she said, and though she still shook like a rabbit, her voice was hard and full of the knowledge that she's gentry. "It is my right to have my maid speak for me. I don't like to speak to someone directly. What if it isn't really him? What if he means us harm?"

"But he'll know my voice isn't yours, and if he knows — "

My lady raised her hand and commanded me to obey on the sacred nine—the eight Ancestors and the Eternal Blue Sky. It's a sin most gruesome to play at being what you're not, and worse than sin to be a commoner speaking as a lady, but what could I do when she commanded me on the sacred nine? She is my mistress and an honored lady besides. I never should have argued. The Ancestors forgive me.

"Khan . . . Khan Tegus," I said through the hole. I stuttered hideously, my words mimicking my scattered heartbeat. "I'm here. Sss —Saren."

I could hear him come closer, and by moonlight, I saw the tip of his boot step on that patch of ground beneath the flap. I thought to be grateful rain had come that morning and the ground was clean.

"My lady, I am so sorry. I came to Titor's Garden to reason with your father, but he wouldn't attend me. His message said only that you are to wed Lord Khasar or no one. I've counseled with my war chief and he says if we attack your father outright, we have a good hope of winning, but we'll incur terrible fatalities on both sides. I thought . . . I imagined you wouldn't want me to do that. I would hate to face your own father and brother in battle."

"No, of course not," I said. His voice sounded so sad, I tried to think of something to cheer him. "Don't worry, we have loads of food, even five bags of sugar and enough dried yogurt to keep a sow and all her sisters happy."

Her khan laughed, sounding surprised to be laughing at all. "That's good news."

"Isn't it? We've fifteen bags of wheat flour, twenty bags of barley, forty-two barrels of salted mutton . . . well, you don't want to hear all about our food."

"And why not? What's better than food?"

"Exactly!" I thought her khan showed good taste and was much more interesting now that his voice had ceased to be so plaintive. "But how are you able to talk to us? Do our guards know you're here?"

"They're asleep," he said. "My men are camped in the woods near here, and I've been watching for hours until all your guards went into their tents to warm themselves. The night's pressing cold. A guard may peek around again, so I shouldn't stay long, but I'll return tomorrow. Is there anything that you need?"

What did my lady need? Sunlight, starlight, fresh air. I said, "Something from outside, perhaps? A flower would be lovely to see."

"A flower? I thought you might want something more than that."

I didn't want to complain about the rats, I wasn't sure if gentry would, so I just said, "We have plenty of food and blankets. We're fine."

"I'm relieved. Farewell until tomorrow, my lady."

"Farewell. . . . " I found I didn't dare say "my lord" in return. It was too much a lie. He is her lord, her khan. Feeling as though I had swallowed a great lump of knotted rope, I brought in the wooden spoon, letting the flap clank shut. Immediately I knelt facing north and prayed, "Ancestors, forgive me, Dashti, a mucker, for lying in words and deeds."

I said it aloud and hoped my prayer would prick my lady a little, so next time she'd speak to her khan on her own.

Why is she so afraid? It makes no sense. She gets worse every day, I think. Perhaps she's tower-addled. I'll go comb her hair and sing the song again for setting a person's brains straight, the one that goes, "Under, over, down, and through, light in the big house, food on the table."

Day 32

He came again last night, whisper-shouting, "My lady! My lady!"

That's not me, so I didn't answer. I stayed on my mattress, mending a stocking, wishing on each stitch that my lady would go speak to her khan herself.

"My lady?" He tapped on the metal flap. It can't be opened from the outside. Rap, rap, rap. "Lady Saren? Are you all right?"

At last she arose from our one chair and stood before me. I kept stitching, praying she would act.

"Speak with him, Dashti," she said.

"Please, my lady . . . " I shouldn't have argued, Mistress would've scolded, but better to be scolded than hanged on the city's south wall. In the city, I learned that's where they execute those whose crimes are so rotten they'd have no hope of ascending into the Ancestors' Realm. The south wall. The wall farthest from the Sacred Mountain.

My lady offered me her hand. How perfect her hands are! I've never seen skin like hers, so soft, no rough spots on her fingertips, her palms like the underside of calf leather. She'll be made to touch nothing harder than water, so I swore by the eight Ancestors and the Eternal Blue Sky. And if what she commands leads my head into a neck rope, then so be my lady's will.

I spoke a prayer in my heart—Pardon me, Nibud, god of order.

She sat on my mattress while I lodged the wooden spoon beneath the flap.

"I'm here," I said. I could see his boot in the puddle of moonlight. It was brown leather, double stitched. It would take a mucker a week

to make one of those boots.

"I didn't wake you?" he asked.

"Oh, no, I never sleep. . . . " I was going to say that I never sleep until my lady does, but I stopped myself.

"You never sleep?"

"No, yes, I do, I just, I mean . . . " I don't know how to lie to gentry.

"That's a shame. I'll say some prayers for you to Goda, goddess of sleep."

His voice went dry. I knew he was teasing me, so I said, "And I'll pray for you to Carthen, goddess of strength. Your ankles look too skinny to carry you." They didn't, of course, but accusing one of having skinny ankles is a friendly insult among muckers, and it felt so natural to say.

I could hear the smile in his voice when he said, "I'll wager it'd take three of your ankles to make one of mine."

"Not a chance," I said. "I have sturdy ankles, strong as tree trunks."

"Show me, then."

So I did. I was wearing a pair of my lady's older slippers, the kind with the toe curled up prettily, so I was proud to let him see my foot when I lowered my right leg through the flap down to my knee. I could feel her khan press his own leg against mine, measuring our ankles together.

"Hmm," he said, "I hate to contradict, my lady, but I think my ankle puts yours to shame."

"Not a chance. And it's not a fair comparison, as you're wearing boots." I was giggling. I couldn't help it, it was so ridiculous, my leg down the dump hole to prove I had sturdy ankles, her khan measuring them, and my lady surely wondering if we're insane. And then when I tried to lift my leg back up, I got stuck, and I felt his hands unhook the tip of my slipper from a metal catch and help raise my leg. He was chuckling by now, too.

"Oh! I brought you a gift."

He lifted something. He used both hands as one does to show deep respect. I thought how he must have had to kneel on the ground to do so. I thought how no one had ever offered me something with both hands before.

It was a pine bough. I reached down and took it. His hands were cold and rough, and I wished I'd had gloves to give him. I thought to hold his hand and sing the song for warmth, but that wouldn't do at all, a mucker holding gentry's hand, and him thinking me his betrothed lady. Not at all.

The Princess in Black and the Perfect Princess Party

The Princess in Black and the Perfect Princess Party The Princess in Black and the Hungry Bunny Horde

The Princess in Black and the Hungry Bunny Horde The Unfairest of Them All

The Unfairest of Them All Forest Born

Forest Born 2 Fuzzy, 2 Furious

2 Fuzzy, 2 Furious The Actor and the Housewife

The Actor and the Housewife The Goose Girl

The Goose Girl Palace of Stone

Palace of Stone Midnight in Austenland

Midnight in Austenland Enna Burning

Enna Burning Dangerous

Dangerous The Storybook of Legends

The Storybook of Legends Princess Academy

Princess Academy Austenland

Austenland The Forgotten Sisters

The Forgotten Sisters The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl: Squirrel Meets World

The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl: Squirrel Meets World Book of a Thousand Days

Book of a Thousand Days Fire and Ice

Fire and Ice The Princess in Black Takes a Vacation

The Princess in Black Takes a Vacation River Secrets

River Secrets The Princess in Black

The Princess in Black Books of Bayern Series Bundle

Books of Bayern Series Bundle True Heroes

True Heroes Austenland: A Novel

Austenland: A Novel The Princess in Black and the Science Fair Scare

The Princess in Black and the Science Fair Scare![[Bayern 02] - Enna Burning Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/bayern_02_-_enna_burning_preview.jpg) [Bayern 02] - Enna Burning

[Bayern 02] - Enna Burning Ever After High

Ever After High Monster High/Ever After High--The Legend of Shadow High

Monster High/Ever After High--The Legend of Shadow High